Increasingly, people and nature face connected challenges presented by larger human populations, higher consumption rates, larger-scale development projects, and diminishing and degrading natural resources, all intensified by a changing climate. In this context, conservation efforts have an opportunity to

enhance the chances for nature to flourish by offering solutions to some of earth’s greatest social and economic challenges. Capitalizing on these opportunities requires a robust, science-based conservation approach that draws on existing strengths, and expands to embrace new disciplines from economics to anthropology, from demography to health.

The Conservation by Design 2.0 conservation process builds off of the strong and widely adopted approach of adaptive management. Adaptive management is a structured, iterative process of systematically testing assumptions to learn, adapt and improve decision-making in the face of uncertainty. From previous, common applications of this approach in conservation, Conservation by Design 2.0 has evolved to incorporate four major advances: 1) explicitly consider linkages between people and nature, 2) design interventions focused on creating systemic change, 3) integrate spatial planning with the development of new conservation strategies, and 4) robustly draw upon and build the evidence base for conservation. We believe that these advances will lead to better conservation strategies and better conservation outcomes, for both nature and people. These four advances are interrelated and each is elaborated upon below.

Today, there are no natural systems without some form of human influence, nor social systems without nature. We increasingly recognize that social and ecological systems and the challenges they face are not just linked, but truly interconnected and co- evolving across space and time. Scientists from many disciplines increasingly use the term ‘socio-ecological system’ to describe coupled human-environment systems. We offer the following specific definition to help practitioners better conceptualize what a socio-ecological system is: 1) a coherent system of biophysical and social factors that regularly interact, 2) a system that is defined at several spatial, temporal, and organizational scales which may be hierarchically linked, 3) a set of critical resources (natural, socioeconomic, and cultural) whose flow and use is regulated by a combination of ecological and social systems, and 4) a perpetually dynamic system with continuous adaptation.

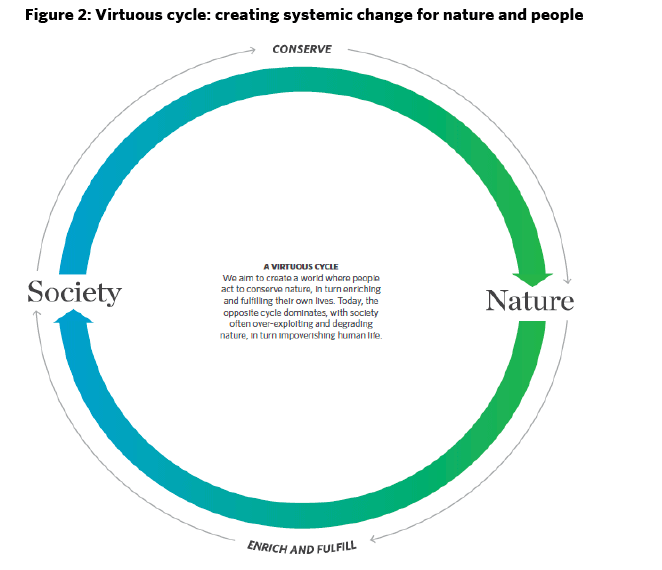

Conservation success is most sustainable when it is the result of systemic change within a socio-ecological system, whereby people recognize the benefits they receive from nature and how their decisions impact nature and its ability to provide these benefits. In turn, through this understanding, people are compelled to act to conserve nature, creating or reinforcing an enduring virtuous cycle. To create this kind of change, the conservation and natural resource management communities must broaden their approaches to explicitly consider the benefits of conservation for people, how alternative decisions will impact these benefit flows, and how to acquire the evidence required for societal recognition of these benefits and to assess tradeoffs. Additionally, in cases where the benefits provided by nature are already recognized by people, but their history of good land stewardship is threatened by an inability to meaningfully engage in management decisions for the lands on which they depend, the virtuous cycle is strengthened by empowering these actors.

Accordingly, the entry point for Conservation by Design 2.0 is a socio-ecological system that provides the bounds for identifying significant problems facing people and nature. Importantly, the scale of a socio-ecological system can be the globe, a major region, a country, or a landscape, seascape, or watershed (e.g., whole system). In addition, for the Conservancy, these systems may be defined in combination with ecological (e.g., a river basin) and/or human (e.g., a city, agricultural system, geography covered by a policy) attributes. This approach requires us to consider the systems we are trying to conserve as a whole. To describe these systems, their trajectories of change, and our ability to influence them towards a more sustainable future, we define several core elements:

- Biodiversity is the variability within and among all living organisms and the ecological complexes in which they occur. Biodiversity includes ecosystem or community diversity, species diversity, genetic diversity and the ecological and evolutionary processes that sustain it.

- We increasingly recognize and understand ecosystem services: the many benefits that flow from biodiversity to people in ways that can sustain, enrich and fulfill our lives.

- Nature encompasses both biodiversity and ecosystem services, and the processes necessary to maintain them.

- Human well-being describes the state in which a person can act meaningfully to pursue chosen goals, enjoys a satisfactory quality of life, and has her or his needs met.

The conservation movement now must aim to transform and strengthen the recognition of the relationship between nature and human well-being. Today, as society struggles to meet growing needs for energy, food, water and other resources, solutions are often found at nature’s expense. In turn, resources are depleted, habitats are degraded, and invaluable species are lost. Damaged nature can then exacerbate food, water and other resource shortages, making unhealthy living conditions and vulnerability to storms, floods and other risks worse. This ‘vicious cycle’ can be transformed into a virtuous one, where nature -- and the benefits it provides—is more broadly recognized as part of the solution to pressing human needs at local to global scales. The conservation approach detailed here is designed to reveal where and when we have opportunities to change or strengthen recognition of this relationship and help create - or reinforce, in cases where they already exist, ‘virtuous cycles,’ through conservation actions.

In the interest of transforming the relationship between people and nature to a more positive one, and to strengthen existing positive relationships, we aim to prioritize conservation solutions that both benefit nature and improve people’s lives. However, in some cases the needs of people and nature will be in conflict. As such, there will still be times and places where we do conservation to protect nature for its intrinsic value, even when there is no obvious, immediate material or economic benefit to people. Further, human preferences and needs vary from person to person and group to group, increasing the likelihood that some individuals and groups may oppose particular projects or that projects will benefit some groups more than others, or put some at risk while others benefit. Such conditions do not necessarily mean that a project should not be undertaken. However, in all our work, we must ensure that vulnerable, disadvantaged, and marginalized people and communities (e.g., low-income communities, indigenous peoples, communities dependent on the local environment, racial and ethnic minority groups, women, children, the elderly) are not harmed and we incorporate social safeguards into project planning and implementation.

We typically think of social safeguards when working with indigenous communities, or primarily in developing countries. These are important contexts for these safeguards as indigenous peoples have collective rights recognized under international law, but there are many others. Nearly all conservation work now engages people as key stakeholders, actors, beneficiaries or potentially negatively impacted individuals or groups, so a review of safeguards at the beginning of any project is worthwhile.

Requesting that teams formally consider social safeguards as part of our conservation process a new practice for the Conservancy, and so we list an abbreviated version of the 11 safeguard questions here. We provide the full list in Appendix C and refer back to the full set of safeguard questions in multiple places in the remainder of the Guidance. If, upon reviewing the safeguards, a team determines the project has the potential to negatively impact any marginalized group, Conservancy staff should seek advice from the Diversity Office about how to proceed. Project teams may want to consider contracting outside expertise if they do not have the capacity to answer the social safeguard questions. Please see Appendix D for additional guidance about working specifically with indigenous people on conservation projects and the further reading and resources section for links to social safeguards guidance of various agencies.

Social Safeguard Questions:

- Has free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) of primary stakeholders been obtained for activities affecting lands and other resources traditionally occupied and/or used by those stakeholders? Please see Appendix C for additional guidance about when staff may need to secure FPIC.

- If applicable, does the project fully consider the dignity, human rights, traditional knowledge, and cultural heritage and practices of people affected by the project?

- If the project contributes to sustainable economic and human development, is it done in a manner that is socially and culturally appropriate for the primary stakeholders?

- Is full consideration given to how to share or distribute benefits from the project equitably, fairly, and transparently?

- How does the project ensure that adverse effects from conservation programs are assessed, prevented and mitigated for affected groups?

- Are all stakeholders being given the opportunity to meaningfully participate in the conservation process?

- If applicable, does the project intentionally benefit gender equality, equity, and women’s empowerment?

- Does the project support transparency and accountability of natural resource conservation and good governance by consistently disclosing and sharing information about intervention plans and results with primary stakeholders in a culturally appropriate manner?

- Does the project comply with applicable local and national laws, international treaties and conventions, and other relevant rules?

- Is there an accountability system that is transparent and accessible for primary stakeholders to share concerns or file complaints about the conservation program?

- If there is a significant risk of adverse impacts that directly threaten marginalized groups, or that threatened the project (e.g., through reputational, financial, or legal risk), is there a monitoring system in place to track adverse impacts?

We tangibly account for people in conservation in several ways in this Guidance. First, we emphasize how environmental changes affect all types of people, and in turn how conservation actions can positively or negatively influence people’s relationship to nature. People can directly and indirectly engage to preserve or restore nature. People can also be affected through our conservation actions and outcomes, whether it is directly through a conservation intervention or through changes in the environment. These people can be wealthy urban residents, rural farmers, corporate leaders, indigenous communities, underserved or marginalized populations, commercial fishers or miners, low- income communities or any other social group. Second, we offer a human well- being framework (see below) to systematically identify how our conservation strategies directly and indirectly affect these groups of people to ensure that we consistently consider all aspects of human well-being and how they may or may not intersect with conservation. Finally, we provide social safeguards considerations (above). Taken together, our framing and tools allow us to articulate and develop plans to maximize opportunities to benefit human well- being and minimize or avoid risks to people caused by our conservation strategies, which helps to increase the impact and sustainability of our work. Throughout this Guidance, we expand on and refer back to these tools and frameworks to integrate people into our conservation work.

Because we have a focus on transforming the relationship between people and nature through conservation, rather than a sole focus on human development, we limit our work to the aspects of people’s lives that are connected to nature. These aspects are not fixed globally, but vary from place to place based on people’s livelihoods and preferences how the project’s socio-ecological system currently functions. These aspects are also subject to change as political, technological, economic, cultural, and other factors shift in the future. The instructions in this Guidance will help practitioners identify which aspects of people’s lives are connected to conservation in each case.

Human well-being is a complex concept. To ensure consistent treatment of human well-being, the Conservancy has developed a framework outlining a set of human well-being focal areas, which are broad aspects of life that collectively define human well-being (Figure 3). For some projects, it may be helpful to break the eight focal areas down into more specific components, such as literacy, employment, income, or nutritional health. Please see Appendix E for more detail (i.e., components within each focal area) and discussion about the Conservancy’s human well-being focal areas and the further reading and resources section for links to other human well-being frameworks. The purpose of the human well-being framework is to aid in systematically considering how nature and conservation affect human well-being, extending our thinking beyond the most familiar facets of human life (e.g. jobs, income), to more clearly identify the aspects of life nature may influence (e.g. nutritional health rather than overall well-being).

Conservancy staff can learn more about integrating human well-being considerations into conservation programs via a series of half-hour webinars conducted in 2015 and now available on CONNECT, here. The Conservation Measure Partnership (CMP) also offers guidance on Addressing Social Results and Human Wellbeing Targets in Conservation Projects, and an updated version will be available by June of 2016.

General Best Practices for Incorporating Human Well-Being

Embedded in each stage of the conservation process, we provide specific recommendations for incorporating human well-being. In addition, several elements of best practice are relevant throughout the guidance:

- Systematically consider the full set of human well-being focal areas (Figure 3) when identifying relevant groups and considering how conservation and nature affect human well-being. Validate human well-being focal areas and components with stakeholders to ensure components are locally relevant. It can be tempting to focus on familiar aspects of human well-being. It can also be tempting to focus only on aspects of human well-being identified by stakeholders which conservation may have little or no power to affect. Finally, it can be tempting to look for available datasets and focus only on aspects of human well-being in those data. Not systematically considering all aspects of human well-being risks missing major human well-being benefits and risks.

- Consider positive and negative human well-being impacts. While it is important to highlight and quantify the benefits that conservation actions can provide to human well-being, it is just as critical to recognize the potential negative impacts. Negative impacts may not always be obvious during the planning stages, so it is important to continually engage with stakeholders and monitor whether and how conservation activities may negatively impact people. Some of the most commonly overlooked negative impacts include less tangible outcomes, such as disempowerment, exclusion of particular groups of people from the decision-making process, or unintentional distributional effects (providing benefits to one group but not another).

- Explicitly consider how to minimize, mitigate, or avoid negative impacts to people during strategy development. The Nature Conservancy requires preventing and mitigating negative impacts to vulnerable people from program activities. Not doing so can lead to mistrust, ill will, misunderstanding or even legal action from stakeholders, and decreases the likelihood that a conservation strategy will be successful and sustainable. It also increases institutional, reputational, and financial risks to the organization. The social safeguard questions summarized above and provided in Appendix C can help practitioners think through whether they are being inclusive, minimizing risk, and taking the right precautions throughout the conservation process.

Explicit in Conservation by Design 2.0 is the expectation that conservationists increasingly seek to effect systemic change within the socio-ecological systems in which they work. Systemic change refers to creating, strengthening, or shifting the social, economic, political, and cultural systems that comprise and sustain a socio-ecological system.

CbD 2.0 clarifies that the future of nature and the future of human civilization are interdependent. However, the major systems commonly used to describe the forces affecting that common future -- economic, political, and social -- do not adequately reflect this interdependence. In short, unless we act to address systemic causes, we are likely to fail in our mission. We are therefore compelled to develop strategies that improve these systems over time. Strategies that successfully strengthen these human elements of a socio- ecological system should ensure enduring conservation outcomes at scale.

Being skilled at systems thinking, a proven approach for developing innovative solutions to messy situations that often seem like intractable dilemmas, is critical in order to be able to develop strategies aimed at achieving systemic change. Systems thinking has been applied to social-ecological systems, governance, and resource use (see Elinor Ostrom's paper, and how her Socio Ecological Systems framework was operationalized to assess sustainability in Baja California Sur); urban ecology (The Nature of Cities); organizations (Peter Senge); health care (WHO) and education (Waters Foundation). We acknowledge here that this field is a growth area for both the Conservancy and perhaps for the conservation community more broadly. You can learn more about systems thinking at

systemswiki.org.

For our conservation work, systemic change can be achieved by, for example, incorporating conservation into economic systems, so that a conservation outcome is produced via new models of “business as usual”. If consumers develop a preference for products that are sustainably harvested, they can incentivize producers to invest in those practices. If regulatory agencies embed conservation principles into their land use permitting process, a potential driver of threat to nature is harnessed to become a potential driver of conservation. By developing strategies to “mainstream” conservation into the everyday policies and practices of agencies, businesses, and communities, conservationists may be able to create far more wide-reaching and durable conservation outcomes that jointly benefit nature and people. By doing so, we seek to drive conservation actions that strategically broaden the constituency of people and organizations who do conservation work, whether they define it this way themselves or not.

CbD 2.0 requires teams to rigorously analyze the various relationships within a socio-ecological system, and think creatively about where there may be opportunities to advance conservation as a solution to major challenges facing society. Indeed, the larger and more recognized and important the “problem for people” is, the more potential impact a “conservation solution” may have – and the more secure the resulting conservation outcome will be. In other words, embedded in socio-ecological challenges may be opportunities to institute a systems-based solution that will also work for nature. The size of the problem may well correspond to the scale of the potential impact. Moreover, a conservation-compatible change in practice or policy can potentially serve as a model that can be replicated elsewhere, enabling conservationists to extend the impact of their investment well beyond the places they directly engage.

We also note that achieving systemic change may take longer, often significantly longer, than the duration considered by a typical conservation plan (e.g., 5-10 years). Consequently, outcomes intended to be met within the planning window will likely increasingly be written as policy, practice or behavior outcomes (e.g., in terms of changed human behavior and changing the sets of “rules” – formal and informal – that guide people’s behavior). When this is the case, teams will be expected to clearly describe in results chains as well as the theory of change the relationship between achieving behavior change, policy, or practice outcomes and meeting the longer-term outcomes for nature and people. Figure 4 gives an example of such a results chain for a generic project that aims to create systemic change for nature and people through a policy outcome. The chain would be further specified in any given project case, and similar chains could be created for projects aiming for systemic change through behavior change or altered corporate or management practices.

When teams are developing strategies that focus on changing the more formal rules (e.g. laws, regulations) that guide people’s behavior, we encourage them to draw upon decades of research in the policy sciences on theories of change of how policy change happens. For example, ORS Impact and the Center for Evaluation Innovation have created practical practitioner-focused examples of common theories of change for how policy change happens in their joint report on ‘Theories to Inform Advocacy and Policy Change Efforts’. Please see Appendix F for more guidance about how to think about human behavior-related strategies and for three common policy theories of change used in Conservancy projects. Finally, please see Evans et al. (2015) for an in-depth discussion of how to frame and measure policy outcomes.

The Conservancy and many other conservation organizations have a strong history in creating maps that identify critical ecological information such as where important biodiversity remains and which locations are likely to be more resilient to climate change. This information remains highly relevant as it provides foundational information for developing actionable plans. Achieving systemic change that benefits socio-ecological systems requires us to harness this spatially explicit information about biodiversity, along with additional types of spatially explicit data, including social, economic, and political data, to develop effective strategies that consider the many dimensions impacting conservation efforts. Conservation has also evolved from a largely protection-oriented practice to one where protection stands alongside many other strategies that may be deployed towards our mission. We now regularly invest in large land deals, the establishment of protected areas, watershed-scale investments in restoration, agriculture, forestry and fisheries best management practices, improving corporate practices, altering development siting, strengthening regulations and laws, and many other strategies, each of which will touch down for greatest impact in different kinds of places. We need a conservation approach that considers these diverse options, their various footprints, and the full set of conditions that determine their likely impact.

In the CbD 2.0 Guidance document we focus on how spatial planning can be integrated with strategy development to tell us what actions are needed where to achieve systemic change. The resultant ‘strategy and opportunity maps’ can show where investments in specific strategies will be most effective. This ensures that investments are targeted to affect the places where they have the most benefit to the larger socio-ecological system and allows robust estimates of the magnitude of change possible with a given strategy. Such mapping also lends itself to comparisons amongst alternative strategies, including cost- benefit analyses.

Accountability to evidence is a hallmark of “science-based” decisions and organizations. An explicit consideration of the quantity and quality of evidence supporting hypothesized conservation outcomes can lead to improved strategies and focused and reduced monitoring demands and can facilitate the identification and management of risks (ecological, financial, reputational, etc.). Conservation strategies aimed at achieving systemic change depend on influencing others to act, and evidence that is relevant and effectively communicated to key audiences can be a critical asset for generating that influence. If available evidence is insufficient to generate that influence or manage important risks, then research and monitoring can be directed to address priority evidence gaps.

Thus, CbD 2.0 emphasizes the generation, collection, synthesis, sharing and leveraging of evidence. We’ve increased this emphasis so much so that this aspect of our work is called out explicitly in three of the five phases (i.e., identify challenges and goals; map strategies and places; adapt). The ability to make robust decisions about investing limited conservation funds requires understanding – and bolstering where needed – the strength of the evidence underpinning a given theory of change.

Here, an evidence base refers to a body of knowledge about how socio- ecological systems behave. The evidence base includes knowledge ranging from scientific assessments to traditional knowledge and may exist in many forms including white papers, reports, peer reviewed literature, primary data, interviews, traditional oral accounts, government records, and social media content. At each stage of the Conservation by Design 2.0 process described below, teams will draw upon and contribute to an evidence base. While Conservation by Design has always included 'capture and share knowledge' as a relevant step within a cyclic and iterative adaptive management approach, by integrating evidence use and capturing learning into each step we expect to foster an organizational culture that helps us learn and share knowledge more consistently and effectively. This Guidance document makes it clear that evidence is an essential input to – and output of – each step.

Over time, and with concerted effort, the conservation community will amass a conservation evidence base that, by virtue of its comprehensiveness and accessibility, will improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the conservation process. Although currently under-utilized, ConservationEvidence.com, Collaboration for Environmental Evidence, Conservation Gateway, and Miradi Share are existing efforts to compile certain types of conservation evidence. Potential benefits of evidence repositories include the more rapid spread of strategies that work in conservation – and ability to avoid repeating past mistakes. Conservation efforts will be less prone to reinventing wheels, or allocating limited resources to demonstrate already well established results. Designing projects so that they build off of best available science, identify and fill the most important information gaps, and disseminate lessons learned to others who may benefit from that experience is critical to increasing the pace and scale of conservation.

Note that the evidence base on its own will not sufficiently disseminate new knowledge about how to accomplish these strategies; we must also commit to proactively sharing what we learn. Conversely, sharing knowledge without a commitment to increasing the evidence is a lost opportunity, and is also insufficient on its own. Here we advocate for evidence coupled with knowledge sharing, as it is this combination of skills and commitments that is needed to truly advance conservation. For this reason, we distinguish the term “knowledge-sharing” from “evidence base”, defined above.

“Knowledge sharing” refers to the spectrum of activities through which information, skills, and expertise are exchanged. Evidence can identify which strategies will work or not in a given set of circumstances, but if that evidence is inaccessible or unknown to others, it will not inform conservation practice broadly. Practitioners often learn about where to find the best evidence and how to apply it from their peers. Knowledge sharing can take many forms including communications at professional conferences or public meetings, online data portals, communities of practice, discussion forums, trainings and guidance, in- person trainings, mentoring, coaching, and workshops, or focused engagements across fields or disciplines as in visiting fellowships, secondments or extended stays with knowledge holding groups. We encourage the use of appropriate practices for evidence synthesis, interpretation, creation, and knowledge sharing throughout the conservation process.

Key Concepts for Building the Evidence Base

Evidence relevant to conservation comes from a wide variety of disciplines and sources. Conservation scientists are typically more familiar with evidence from the fields of conservation biology, ecology, evolution, and spatial planning, and may assume ‘good’ evidence is found only in peer-reviewed publications. However, conservation now must draw from evidence produced by many more diverse fields including health, poverty alleviation, education, demography, psychology, economics, anthropology, and sociology, among others. In addition, much conservation knowledge exists as traditional knowledge held by local communities, stakeholder groups (e.g. farming coalitions, business roundtables, extension networks) or indigenous peoples. Teams should place equal effort on identifying relevant evidence across disciplines, sectors and knowledge sources, as appropriate.

Evidence base assessments should not perpetuate confirmation bias. The conservation community is prone to elevate successes and less frequently shares information about failures. Teams conducting evidence base assessments should aim to identify all relevant evidence relating to an assumption; including evidence that supports it and evidence that refutes it. Given the potential for hidden bias for affirmative results, we encourage conservation teams to intentionally seek out evidence that may counter leading assumptions of how strategies will create positive impacts for nature and people. This evidence may otherwise be overlooked, leading to false and misleading interpretations of existing knowledge.

An assessment of the evidence base creates transparency. It is critical to differentiate between proposed actions that are strongly supported by evidence, those where the knowledge base shows conflicting information (some showing the action’s effectiveness and some showing failure), and those where no evidence exists. This transparency of status will allow conservation teams and managers to make informed investments, define monitoring needs, and make risk-related management decisions.

The emphasis on evidence should not limit innovation and creativity. Innovation is a key element of conservation success, and requires generation and testing of novel ideas. By definition, such new ideas will not have a full body of evidence supporting their effectiveness for conservation. Those novel strategies may nonetheless be worth investing in if the potential reward is great enough. A commitment to evidence must not stifle innovation. However, for projects with a limited evidence base, it is especially important to invest in building the evidence base through well designed and sufficiently funded research and monitoring.

Evidence must meet minimum standards to be considered evidence. To be considered evidence, the assumptions made by the conservation team must have been measured or observed. Opinions that something should work, even when contained in a conceptual peer-reviewed paper, do not count. For example, if sustainability standards are expected to change corporate behavior, conservation teams would look for evidence that sustainability standards had been shown to create change in corporate behavior in real world cases. Papers identifying a conceptual pathway through which such change could happen do not provide such evidence. Reports or agreements where corporate leaders have pledged to change behavior do not constitute evidence. Papers or reports that show adoption of different practices as a result of sustainability standards do constitute evidence for this assumption.

Not all evidence is created equal. Evidence is strong when we have confidence that additional data will not reverse our conclusions. This is generally the case where there are consistent findings across multiple studies (e.g., meta-analysis) or where effects are far too large to be attributed to chance alone. Studies where rigorous experimental designs are used (including before-after comparisons as well as an appropriate control group) also generate confidence. Although there is not yet consensus among conservation practitioners around a standardized approach to evidence grading at this time, expert judgment should consider these factors when assessing strength of evidence. In this version of the Guidance, a basic method for characterizing evidence quantity using this minimum standard is presented (e.g., strength of evidence for results chains). Future Guidance versions will include methods for assessing evidence quality, an equally important element of evidence assessment.

The required quality of evidence will vary from case to case. The strength of evidence needed to provide confidence in a decision varies from decision to decision. Strong evidence is not equally important in all cases. For example, decisions that present high financial or reputational risks, or risks to vulnerable stakeholders, should be held to a higher evidence standard than those with relatively low risk. The way in which evidence is intended to be used in a strategy also will determine the strength and type of evidence required. Thus, a key consideration for conservation teams is whether the available evidence is “sufficient” for the assumption, decision or strategy it supports. Factors that determine sufficiency include organizational risk tolerance and the information requirements and risk tolerance of stakeholders.

A well-developed evidence base can reduce and focus monitoring needs and minimize costs. Given limited conservation resources, teams should focus research and monitoring efforts on high priority information gaps, with priority being determined by such things as the stakes of being wrong, and the information needed to influence key actors (see Monitoring section). As the evidence base for conservation builds, we will be able to continually shift investments towards filling key evidence gaps and away from measuring well-documented outcomes.

General tips

Design a project to generate evidence. Teams can accelerate the development of a Conservation Evidence Base by thinking about their conservation engagement as a “hypothesis”, and building into it elements of good experimental design, such as: a clear understanding of the assumptions being made in the theory of change; a hypothesis of the change we propose to make through an intervention; identification of controls or counterfactuals for comparison with the project; adequate monitoring to detect change; analysis to determine effect; and, an investment in communication of results, regardless of the project’s “success.” Sharing evidence of failures is just as important – if not more so- than sharing evidence of success.

Finding evidence and building an evidence base. Sources of evidence are many, and may be difficult to locate. Some may be found via literature review using standard scientific search methods, while other evidence will be found in reports, public documents, white papers, data bases, oral histories, social surveys, and many other repositories. Teams should document the methods used (e.g., keywords, databases, key informants engaged, interviews conducted, social media searches) in building the evidence base for their project, and ensure that their synthesis is designed for accessibility and peer review. Because many conservation engagements aim to address similar systems and issues, early investment in comprehensive evidence review and synthesis on major themes would benefit many projects.

Understand the context for sufficiency of evidence. The sufficiency of evidence depends on the context. What will the information be used for? There are five categories of use that should be considered: 1) reducing uncertainties in the theory of change and improving adaptive management; 2) avoiding and mitigating negative impacts; 3) managing legal or reputational risk; 4) reporting to funders and other philanthropic uses; and; 5) influencing others. The specific circumstances within each category should be considered. For example, who are you trying to influence? If you are trying to encourage engineering and insurance companies to alter premiums based on the presence of natural infrastructure for flood risk reduction, this will require rigorous evidence demonstrating a cause and effect relationship. In contrast, the testimony of constituents may be sufficient evidence for convincing politicians of the value of a particular conservation plan.

Experimental design principles are needed to provide evidence of causation. In order to estimate the impact caused by an intervention, it is generally necessary to have data prior to and after the intervention, and to have the same data from a comparable control group that does not receive the intervention. Experimental design and statistical rigor is related to the required level of strength of evidence. Additional guidance on experimental design and rigor is provided in the Monitoring section and in Appendix G.

Capturing and sharing knowledge. Knowledge management and transfer can be a highly leveraged conservation strategy – ensuring that the broader conservation community benefits from experience and investments regarding what works and what fails. Learning should occur in all phases of CbD 2.0. Conservation teams should be attentive to advances in knowledge that occur during their application of the process, and develop the systems and discipline to capture those advances. Documentation and dissemination of information may take a range of forms. Conservancy staff can find guidance and tools for knowledge management and sharing in the Organizational Learning Community on CONNECT, here.