Pedro Bara Neto, Green Growth Program Manager, Brazil Conservation Program

pedro.baraneto@tnc.org

Background

The Tapajós River basin drains the central Brazilian shield through three states (Mato Grosso, Pará and Amazonas) and 65 municipalities. The major rivers in the basin are: Tapajós, Jamanxin, Juruena and Teles Pires (Map 1). The Tapajós is one of the largest tributaries to the Amazon basin and has a very rich and diverse flora and fauna, transitioning from Brazil’s savanna (known as “cerradoâ€) to Amazonian lowland rainforest and savannas, and covering almost 6 percent of the Brazilian territory. The Tapajós River is not only a main source of life for over 1.4 million people living in the basin, but is also a source of pride and joy for Brazilians. Over 60 percent of the Tapajós basin is covered by large tracts of forest, considered of global importance for both aquatic and terrestrial biodiversity. The basin contains 30 conservation reserves (national and state) and 42 indigenous lands

Map 1. The Tapajós River Basin and tributaries

Because of the abundant water availability and hydraulic power, the Tapajós River and its tributaries have been identified as having a large potential for hydropower development. Estimated at over 28,500 MW; the Tapajós basin potential is considered a key part of Brazilian strategy for meeting electricity demands in the next 20 years. Forty or so large dams on the main rivers and 52 small dams are being planned in the basin without an integrated strategic vision. The extent of their cumulative impacts, or even individual impacts, is unknown. These dam projects will lead to the inundation of significant land areas that sustain indigenous and other local populations and will affect river flow, water quality, fish migration, and access to habitats upstream.

The lack of a strategic vision for this basin calls for action that links licensing and decision-making with system-scale, integrated planning of infrastructure development to determine sites for hydropower development that are the least impactful to people and biodiversity. In order to gain a clear understanding of the decision-making context in which The Nature Conservancy (TNC) was working, TNC conducted a situation analysis of the decision-making processes for hydropower development in Brazil. In this analysis, we characterized the decision makers, analyzed the most relevant processes and determined next steps, which guided our policy and technical engagement strategies.

Summary of Approach

Based on publicly available information, we characterized and mapped the key processes and institutions charged with implementing these processes; and, based on the results, identified a set of decision-makers and processes that will influence hydropower development in the Tapajós basin.

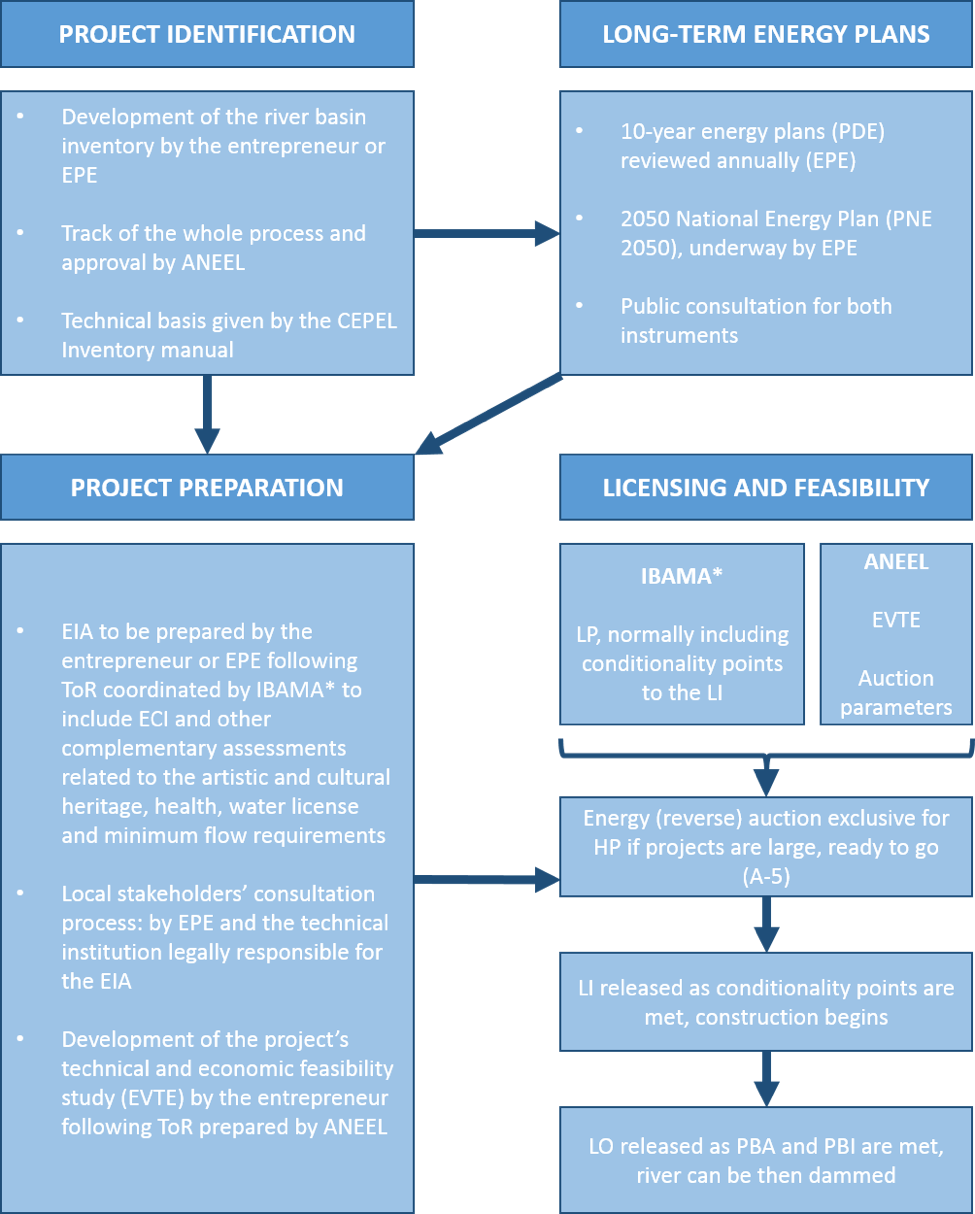

Our findings demonstrated that hydropower development in Brazil occurs after several key decision-making processes along the project identification and preparation cycle. These processes include those for deciding long-term energy development plans, river basin inventories, feasibility studies, consultation, licensing, compensation and benefits sharing, which is supported by a social sub-credit, a part of the financing by BNDES.

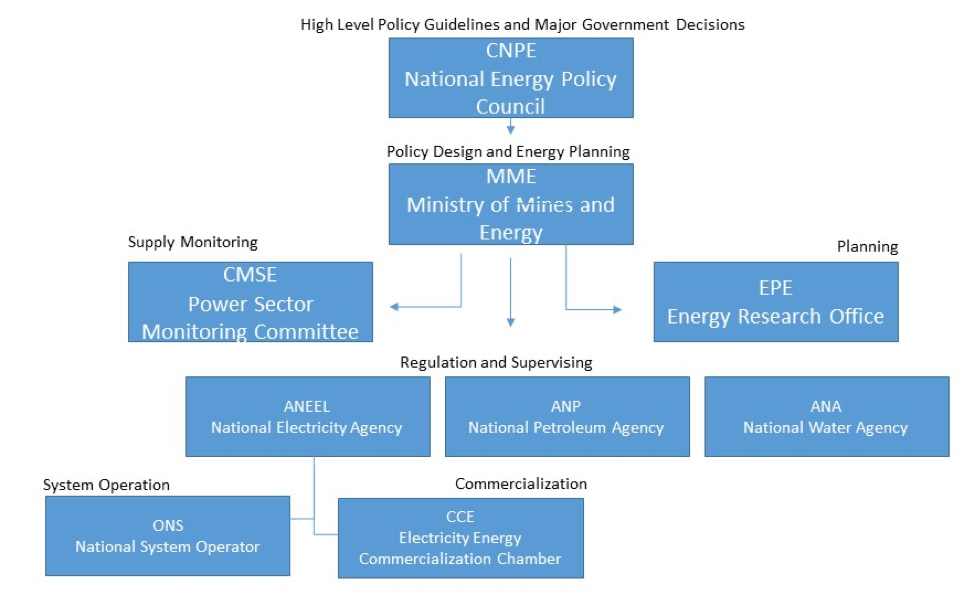

We also identified that the main decision-making entity in the country related to the energy sector is the Ministry of Energy and Mines (Figure 1), but characterizing and mapping out the individual agencies, their authority, and linkages to each other and decisions was necessary to better understand the most relevant institutions for engagement through Hydropower by Design.

Figure 1. General Organizational Structure of the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME)

>

>

Details on these agencies include:

The National Energy Policy Council (CNPE) is an advisory body to the Ministry of Mines and Energy. It oversees approving supply criteria and "structural" projects.

The Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) has the overall responsibility of establishing policies for the electricity sector.

Power Sector Monitoring Committee (CMSE) is tasked with monitoring supply continuity and security.

The Energy Research Office (EPE) is the federal energy planning entity responsible for developing the integrated long-term planning for Brazil’s power sector. Its mission is to carry out studies and research services in the planning of the energy sector. It provides input for planning and implementation of actions by the MME. It provides technical services to support energy sector planning, including supporting hydropower, oil and gas, coal, other renewable sources and energy efficiency. In addition, EPE looks at specific assessments to support energy auctions (mainly related to the auction format and the qualification process) and identifies and prepares specific projects. The main documents prepared by EPE that are most pertinent to hydropower development are the National Energy Plan (PNE) and the 10-year plan (PDE).

The National Electricity Agency (ANEEL) seeks to “promote the enabling conditions for the electrical energy market to develop with equilibrium between the economic agents and the benefits to civil society.†ANEEL is responsible for regulating and controlling the generation, transmission and distribution of power, while ensuring it is in compliance with existing legislation and with the directives and policies dictated by the Central Government. Within ANEEL, the Superintendence of Concessions and Generation authorizations (SCG), responsible for registering, analyzing and approving river basin inventory studies, feasibility studies and basic design of large and small hydroelectric dams, was identified as a key decision-making body to work with for Hydropower by Design.

The National Water Agency (ANA) is responsible for granting the DRDH, which translates to “declaration of reserve of hydraulic availability.†This declares that there is enough water in a river to be dammed or diverted and takes into consideration the needs of other water sectors for the resource.

The National System Operator (ONS) is a non-profit private entity which coordinates and controls the generation and transmission installations in the National Interconnected System. ANEEL controls and regulates ONS.

.The Electricity Energy Commercialization Chamber (CCEE) operates the commercial energy market. The role of the CCEE was initially to create a single, integrated commercial electricity market, which was regulated under published rules. CCEE is now also in charge of the auction system. The rules and commercialization procedures that regulate CCEE's activities are approved by ANEEL.

Details on the processes include:

We examined the 10-year plan for energy, which demonstrated that, over the last five editions, clear trends could be found. These trends included an interest by planners to:

- Diversify the electrical energy matrix with an augmented share of other renewable sources, such as biomass and wind power and, more recently, the introduction of concentrated solar projects;

- Avoid territorial conflicts with conservation units and indigenous territories in the Jamanxin and Juruena rivers in the Tapajós river basin

- Develop a plan with a multitude of basins, including those located in the Northern hemisphere, where there is potential for hydrological complementary, as annual seasonal hydrological variations among basins at the national level is concerned; and

- Increase the “dispatchability†of the electrical energy system (especially more recently and intensively due to the water crisis), with a corresponding increase in the share of thermoelectric plants.

We also analyzed how river basin inventories – the suite of dam projects that would go into the pipeline of review, auction, and license – are generated, and found that the inventory studies entail four phases: planning, preliminary studies, final studies and the integrated environmental analysis (AAI). The preliminary study delivers a selection of dams based on an energy cost-benefit ratio (ICB) and a socio-environmental negative impact (IAN) indicator, both developed for each dam development option. The final study then examines a selected alternative by looking at its cumulative and synergetic effects. This is further assessed by the AAI.

The role of the AAI is to identify potential conflicts that may arise from the cumulative and synergistic analysis during the final study phase, and to develop future scenarios for the basin with and without the selected hydropower development alternative. The AAI does not deliver a list of projects to be avoided, as one would expect, but a set of guidelines for the electrical energy sector to follow and recommendations for other sectors to deal with potential conflicts, information gaps, vulnerable areas, institutional weaknesses, economic potentialities, among other risks and opportunities identified along the evaluation process. In the absence of an integrated effort to make developers follow the guidelines and recommendations, the future scenario turns out to be nothing more than a theoretical exercise. Thus, we discovered that although there is a norm within Brazil to conduct a river basin inventory, the lack of a clear methodology and requirement to follow the recommendations laid out in the AAI prevents hydropower development from being planned in a way that diminishes these risks.

We also sought to understand the process for developing the inventory of dams. The identification of dam projects to be considered for development is decided by EPE, in the initial stage of inventory development. At this stage, the current considerations account for energy production, but not for social and environmental considerations. As such, The Nature Conservancy has identified this stage as an opportunity to include social and environmental values when developing the suite of dam projects that will go into the development pipeline.

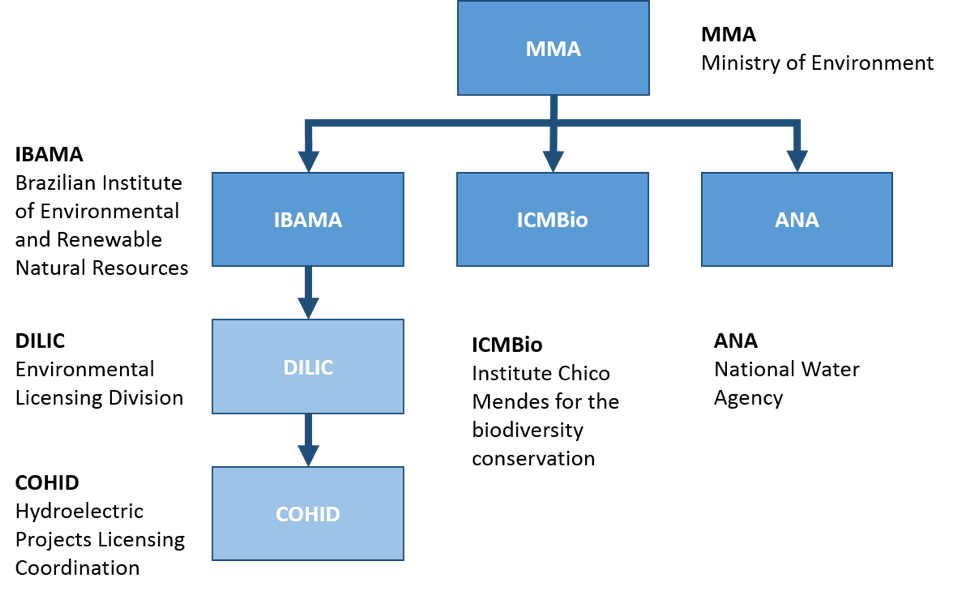

To further understand the decision-making context, we characterized and mapped the second most important decision-makers and decision-making processes that influence the basin. These processes and institutions are at the Environmental Sector Level in the Ministry of Environment and its associated agencies.

Figure 2. Institutional framework of the Ministry of Environment

Details on these agencies include:

The Ministry of Environment (MMA) is tasked with promoting the adoption of principles and strategies for the protection and restoration of the environment, for the sustainable use of natural resources, for the valuing of environmental services and for the inclusion of sustainable development in public polices, in a participative, democratic and transversal way, at all levels and instances of government and society in Brazil.

The Brazil Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) is an administrative arm of the MMA. It plays a dominant and coordinating role for the hydropower project licensing process.

The Chico Mendez Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) is an additional administrative arm of the MMA. Along with IBAMA, it oversees the National Environmental System (SISNAMA), which is a convener of agencies and institutions to implement principles and norms for the environment, imposed by the constitution. ICMBio is charged with protecting Brazil's natural heritage, promoting ecologically sound management practices, and endorsing biodiversity conservation through research and education. It primarily manages federally protected areas, and is responsible for proposing, implementing managing, and monitoring conservation units as part of the National System of Conservation Units.

The National Water Agency (ANA) is legally liable for implementing the National Water Resources Management System, created to ensure the sustainable use of rivers and lakes in Brazil. As part of their work, ANA carries out actions of management support and monitors and plans for water resources. In addition, ANA offers information to improve the performance of Brazil’s water resources management agencies and the sectors that use these resources. ICMBio and ANA compliment IBAMA in its hydropower project licensing process.

Details on the processes include:

We evaluated the Presidential Decree # 8437/20158, which defined new limits for IBAMA to license hydropower projects, and found that it increased the authority of the local Environmental Secretariats (SEMAs) in the decision-making process of hydropower development.

Finally, we also examined other sectors to identify possible areas of influence. This included gaining an understanding of the Indigenous People National Foundation (FUNAI) and its power to influence development licensing, the Palmares Cultural Foundation (FCP), the National Institute of the Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN) and the Ministry of Health (MoH), as representatives of community voices. In Brazil, indigenous territories represent about 20 percent of the Amazon biome, or about 1 million sq. km. with a good amount located in remote areas which are becoming more exposed to the development frontier, this issue has become a critical when considering the licensing process of hydropower projects in the Amazon as it may have constitutional implications and potential reputational risks for developers and the Brazilian government. In addition, we identified that public attorneys play an important role in enforcing international and national commitments for hydropower development in the Amazon, in particular those related to the rights of indigenous’ people.

Products/Results/Outcomes

From these analyses, we then developed a synthesis map to strategically guide our thinking during stakeholder engagement.

Figure 3. Synthesis of processes, actors and instruments

Next Steps in the Work

Based off our understanding demonstrated in this synthesis map, we developed a list of key actions to influence decision-making in hydropower development. This included identifying the main gaps in the decision-making process, improving scientific information to support decision-making related to biodiversity conservation at the basin level, and developing strategies to support civil society’s participation in the decision-making process, not only at a project level (EIA specifics), but also at the regional conservation and development level. We also identified where we should advocate full implementation of the legal framework to further promote transparency and public consultation of long-term energy plans and terms of reference for the EIAs and EVTEs (the technical and economic feasibility studies for potential projects).

We have begun advancing the EPE-civil society agenda with the civil society Infrastructure Working Group.

There is a clear need in Brazil to rethink how the cumulative impact assessment is completed, which occurs after the basin inventory, rather than before. The most promising proposal is to include social and environmental considerations in the economic analysis of potential projects so that these potential projects account for the cumulative effects once projects are identified, instead of after the fact.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Approach

Strengths: This strategy was successful because Brazil’s public electrical energy sector is inherently characterized by strong organizations and a comprehensive legal framework with a reasonable level of transparency. Given this, much of the information that informed this mapping process was relatively easy to come by. In a context where information is not as readily-available, this kind of mapping would most likely require more face-to-face engagement with key actors to best understand the development environment, so may take longer than the process described in this case study.

Weaknesses:While the implementation team had access to much of the information needed to conduct this mapping, the main weakness in the process is the asymmetry between the public electrical energy sector and other public decision-making agencies, particularly in relation to decisions affecting the environment and indigenous peoples. This affects, then, not only how the information is mapped but, more importantly, how these processes are enforced.

Suggestions for Others Considering a Similar Approach

A major lesson learned from this process is to remember, as the implementation team, to understand the distinction between how comprehensive one needs to be in doing a mapping like this and to what extent the legal decision-making processes respond, or are resilient to, the political and economic context of the region/basin/country, etc. because these can change the system in which the team is operating and it is important to be flexible.