Emily Chapin, The Nature Conservancy, Global Water team

emily.chapin@tnc.org

Introduction and Background

The start of a technical Hydropower by Design (HbD) analysis, beginning with the translation of stakeholder interests into metrics, does not always require that the government express demand or interest prior to its inception. In some situations, the purpose of doing a HbD analysis is to catalyze government-led demand for a more comprehensive analysis. This was the case of the short-term research report that the Nature Conservancy completed in Myanmar in collaboration with the United Kingdom's Department for International Development (DFID), the University of Manchester and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

Myanmar is a country in South East Asia with a population of 51 million people and has a low to middle income. About one third to a half of the population has access to electricity. While the country has the potential for an estimated 100 GW of hydropower capacity, less than 10% of the potential has been harnessed to date. Its hydropower potential comes from two large rivers, the Irrawaddy and the Salween, which are also critically important to sustaining livelihoods for many people in the country. In fact, Myanmar ranks 4th in the world for fish harvest from freshwater rivers. Furthermore, irrigation, water supply and navigation are also important resources provided by the country's rivers.

In 2015, at the earliest stage of the team's report development, Myanmar was in a phase of political transition, as a new democratically-elected government was taking office from one that was previously led by Myanmar's military. While these changes were a source of uncertainty, the project team saw this as a unique opportunity to demonstrate to the incoming government our approach to system-scale planning for water and energy. In the previous decades, the government's hydropower planning strategy was primarily focused on maximizing energy generation. Yet the government ran into many challenges in the 2000s when Chinese investors showed interest in financing large infrastructure projects that threatened livelihoods and the security of many ethnic minorities. One notorious project is the Myitsone dam, located at the confluence of the Mali and N'mai rivers, which was ultimately suspended due to civil society protests in response to the project's looming environmental and social risks.

The new democratic government in Myanmar has indicated that it will emphasize sustainable energy development moving forward. The purpose of our work in Myanmar was to develop and apply a framework for system-scale planning to share with the new government and show that there are ways to ensure better outcomes for hydropower infrastructure while still protecting the country's environmental and social assets. The report's intent was to demonstrate the potential for more sustainable hydropower planning and garner interest from the government to do a full-scale analysis.

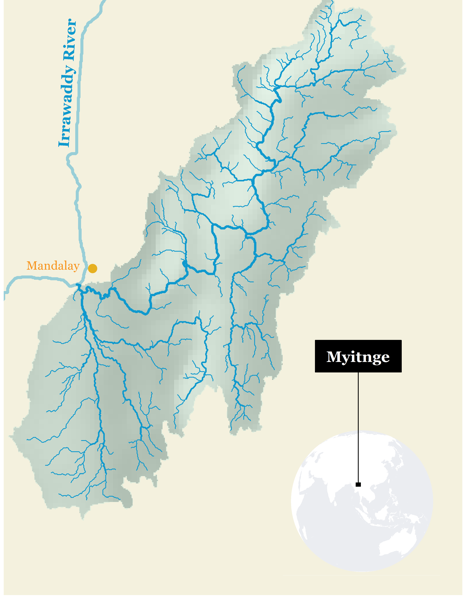

Map 1. Map of Myitnge river basin

Summary of Approach

The four phases of the project capture the team's process of completing the HbD analysis in Myanmar. Drawing from Component 1 (Embed within planning and decision-making processes), the first phase was a scoping visit to the country to start initial discussions about approaches and cooperation with stakeholders. Since the timeline and resources available to do this project did not allow for a comprehensive HbD analysis as they are outlined in Component 3 and 4 for the entire country, the team selected the watershed of a medium-sized tributary of the Irrawaddy river, called the Myitnge river. The Myitnge river comes from the Shan plateau in the north-eastern region of the country and its confluence with the Irrawaddy occurs shortly downstream of Mandalay. The basin already has one major operational hydropower dam (Yeywa - the largest active dam in the country with an installed capacity of 750 MW), another dam under construction and proposals for three new dams.

As suggested by Component 2 (Engage stakeholders and understand interests and objectives), the second phase of the project was to gather as much background information on stakeholder interests and objectives within the river basin through interviews and research where possible and begin the process of collecting data in the selected basin. The team quickly discovered that there is a significant lack of publicly available data for the Myitnge and for the entire country. Although the team tried to collect data from local partners and stakeholders, the team primarily relied on global-scale data for the analysis. One of the primary reasons why the analysis was intended to be illustrative and not inform actual government decisions about hydropower dams on the Myitnge river is because global-scale data generally do not provide the appropriate resolution and accuracy necessary to inform local decisions.

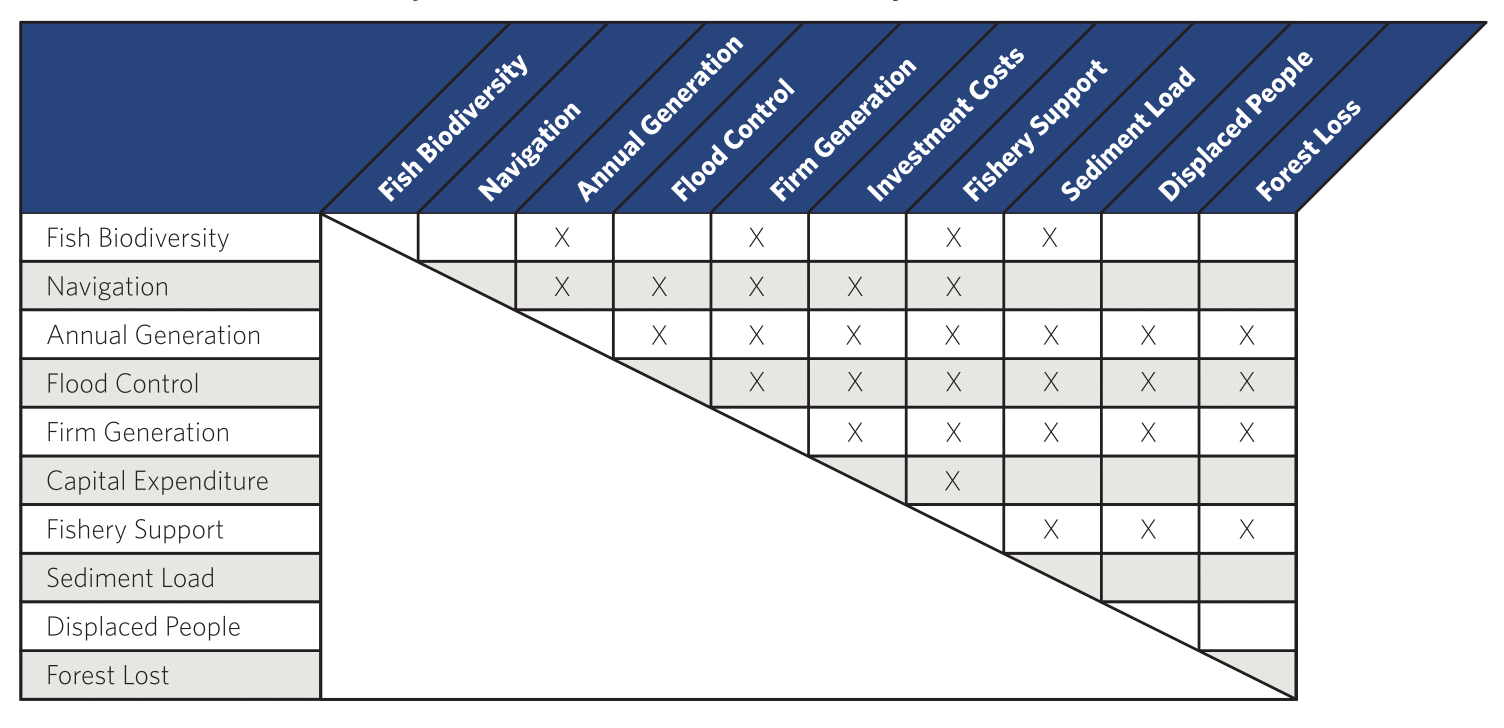

During the third phase, the project team met in-country to carry out the HbD analysis with the goal of also conducting stakeholder consultations, field research, workshops and training events and to begin the drafting the report. The data collected in the previous phase of the project were used to generate 10 metrics that aim to assess the direct and downstream spatial footprint of current and potential hydropower development and its impact on theoretically-important resources and values to stakeholders, albeit informed by initial stakeholders in phase 1 of the project, in the Myitnge basin (see component four for more information on the direct and downstream spatial footprint). These metrics constitute a wide range of interests, including flood control, navigation, fisheries, sediment delivery to the Irrawaddy delta, loss of forest cover, displacement of villages, impacts to local fish biodiversity, annual power generation, and infrastructure costs. A geographic information system (GIS) was used to generate each of these metrics across a range of potential development portfolios, which consisted of current hydropower dams and proposed dams in the river basin.

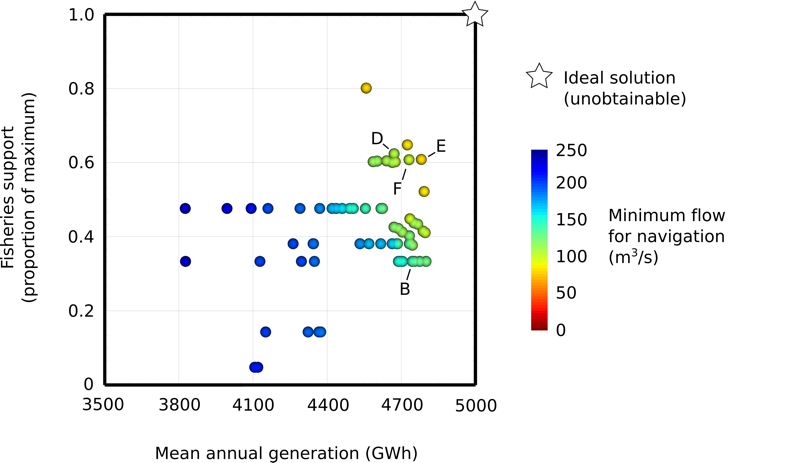

We also worked with partners at the University of Manchester to build a river basin simulation model to represent the main channel of the river basin and used the model to evaluate the tradeoffs across the metrics for many different portfolios. At this stage, we incorporated metrics in the simulation model that are dependent on the dam operations in each portfolio, such as firm generation and alteration to downstream flow regimes. The simulation model was paired with a search algorithm to select a large number hydropower options and from these options, the team could identify the highest-performing options—those that balance costs and benefits for different stakeholders, while maximizing the efficiency of water use. Then, we used visualization techniques, such as trade-off curves, to help decision makers understand and find options that balance performance across a range of metrics.

Figure 2. Summary table of the metrics used and which ones experience tradeoffs with other metrics

Figure 3. An example of one of the tradeoff curves highlighted in the report between fisheries, annual energy generation, and minimum flows for navigation. This figure helps to demonstrate how a stakeholder might assess the tradeoffs across three different performance metrics for multiple scenarios. For example, there is an option F between D and E, which provides greater energy generation than D and comparable generation to E, while also performing more favorably for navigation than option E.

After running the models and producing tradeoff results, the project team hosted two interactive workshops: one with ministerial representatives from the Ministries of Environment, Energy, Agriculture and Irrigation, and Transportation, and the second included representatives from Myanmar's civil society. The intent of both workshops was to cultivate feedback on the approach, results and implications of the report's outcomes to the future of energy planning in Myanmar. The ministerial representatives expressed interest in the proposed approach and welcomed more cooperative and closer coordination across ministries to create more efficiencies and synergies in watershed planning. Attendees at the civil society workshop expressed cautious consensus in support of the report. They had doubts about the validity of the data and shared their concern for the paucity of data in the country. Attendees from both workshops questioned who could be the appropriate party to govern the process of coordinating a more comprehensive tradeoff analysis.

Since the release of the report, the project team has been building relationships with key stakeholders and using feedback from the workshops and the interest it catalyzed, as demonstrated by the demand to implement a more concerted strategy for energy planning. The development of a comprehensive strategy is underway and will build off the foundation generated by the report.

Strengths and Weakness of the Approach

Although the technical analysis are based on global data sources which often is not overly reliable data, the core of the analytical approach demonstrated its feasibility and accessibility as an effective tool to help decision makers bring together stakeholders and transparently balance tradeoffs regarding their hydropower options. A benefit of the Myanmar approach is that it was done with a relatively modest budget and project team but was still successful in generating public interest in a plausible framework for system-scale planning for water and energy. While the results were illustrative, it did catalyze awareness and early-stage interest from government and civil society representatives and thus, created encouraging conditions to pursue a more robust application of HbD in the future.

One recommendation to other groups who are considering conducting an illustrative HbD analysis is to engage with decision maker audiences as repetitively as possible. After completing the HbD report and workshops in Myanmar, the project team recognized that greater uptake from representatives of Myanmar's ministries might have been achieved by more workshops and more opportunities to build relationships. More frequent opportunities to interact with decision makers would also make the process more hands-on and give the decision makers more ability to influence the direction of the analysis. Due to the paucity of data in Myanmar, it was also imperative that the project team be as transparent as possible about the sources of data used and that the report was not meant to inform actual hydropower planning decisions. Other teams that plan to do a similar HbD analysis should also strive to be as transparent as possible.