Juliana Delgado, Science Coordinator, Northern Andes and Southern Central America

jdelgado@tnc.org

Background

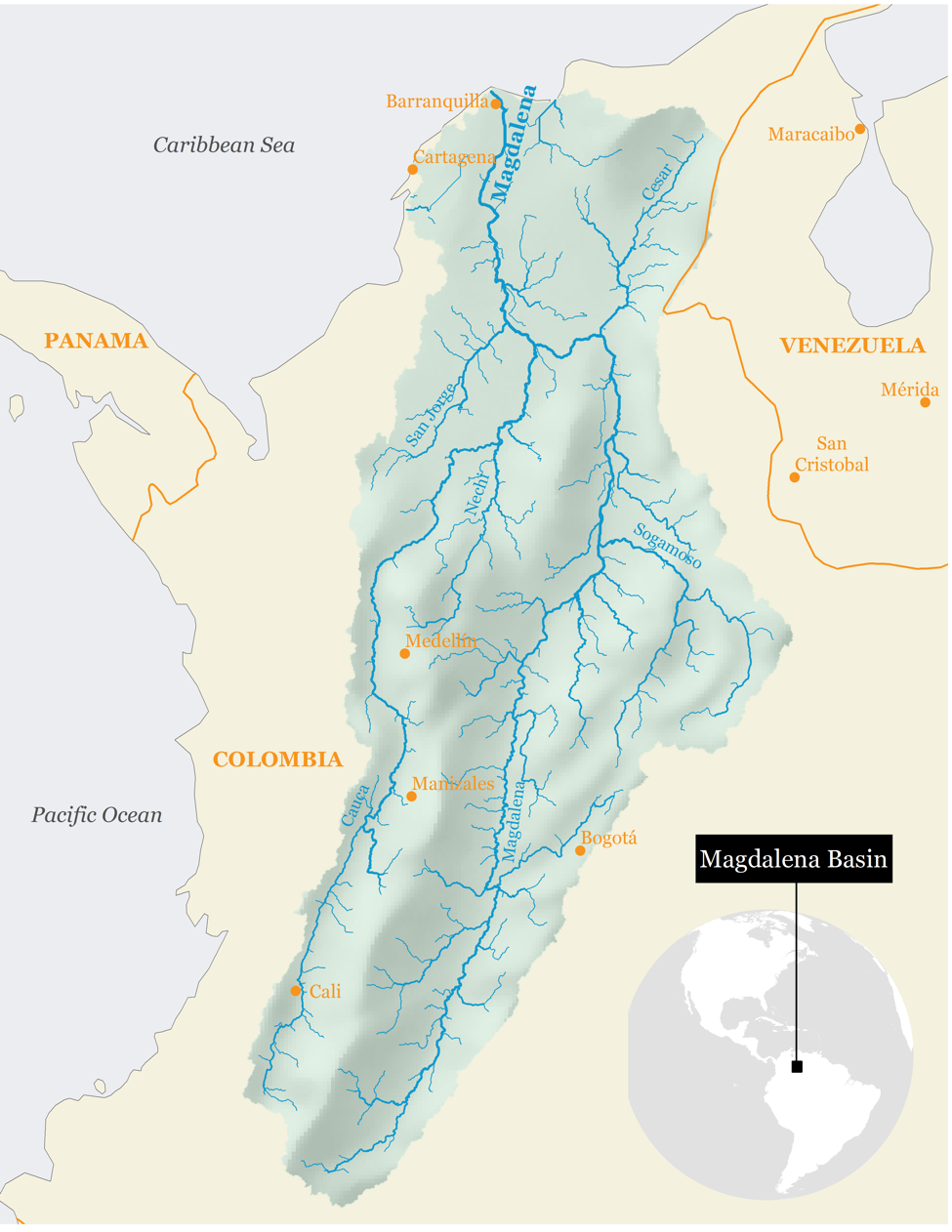

This case study highlights the process of The Nature Conservancy’s work to understand the interests and objectives of different stakeholders in Colombia, and demonstrate how the implementation of Hydropower by Design (HbD) encompasses a broad range of economic, environmental, and social values in the Magdalena basin. This approach demonstrates that collaboration with a range of partners -including governmental agencies, research institutions, basin communities, and other NGOs -greatly strengthens the relevance and positive impact of the HbD process. The Magdalena is the 5th largest river in South America, with a 1,500km main stem, more than 100,000km of rivers and a mean annual flow of 254,300cu ft/s at the mouth.1

The Magdalena basin forms the economic, social, and cultural heart of Colombia; it covers 24 percent of Colombia’s national continental territory and 30 million people reside within the basin. The region’s fisheries and flood-dependent agriculture interweaves both economy and society, producing 80 percent of the country's gross domestic product. The riverine ecosystem directly supports land-based livelihoods including livestock and seasonal crops. Effective management of the basin is a national development priority, as it is closely linked to food security, energy production, and water management.

Map 1. The Magdalena-Cauca Basin and tributaries

Summary of Approach

The Nature Conservancy has worked closely with the government, hydropower sector, and civil society groups in Colombia since 2008. This broad and sustained engagement with multiple stakeholders across different scales –national, regional, and local –as well as both private actors, such as the hydropower industry, and public government agencies, is invaluable in Colombia’s HbD implementation process. In complex basin systems like the Magdalena, stakeholders must be part of deriving integrated management solutions; if they are excluded, the ‘system’ does not learn and cannot adapt to change. Stakeholders usually refer to a subset of the broader public with a clear interest in the outcome of a decision-making process. Participation may be conceived as a process in which stakeholders influence policy formulation, alternative designs, investment choices, and management decisions affecting their communities to establish a necessary sense of ownership.2

Encouraging the adoption of HbD tools and practices to improvethe development of sustainable hydropower plans required identifying the short and long-term interests of relevant stakeholders. In this approach, wesought to align HbD adoption with broader government priorities including: climate change mitigation and adaptation; green growth strategies; implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals; and Colombia’s commitments to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The Conservancy started by engaging regularly with key institutions and conducting workshops to identify how HbD fit into national planning, and how these high-level mandates guide government and industry priorities.

The development of SIMA3 – a decision support system for the Magdalena – is illustrative of how The Nature Conservancy worked to understand the interests and objectives of different stakeholders. By approaching potential users in the initial phases of SIMA’s development, we received iterative input on the design of the tool. Discussing the concept with different groups effectively built interest and understanding, and stakeholders wanted to participate and offer feedback.

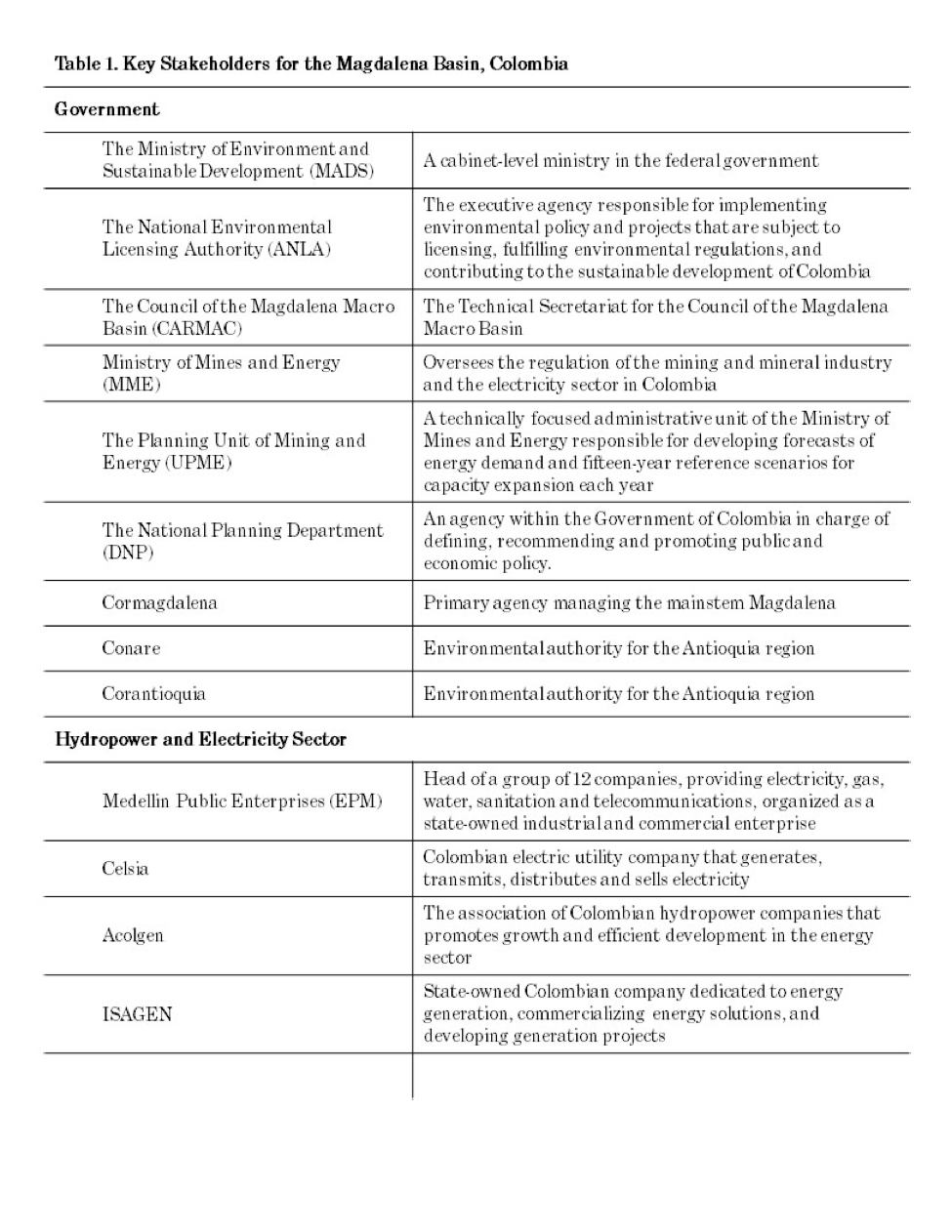

Regular stakeholder workshops further solicited input on the tool’s design over the course of its development. The purpose of these workshops was to encourage the stakeholders to be involved in an iterative, long-term process and demonstrate that the Conservancy was responsive to their needs. For this to be successful, the work of our staff from policy and external affairs, as well as the science and strategy staff, was key to support regular communication and meetings. Workshops were organized within our planning process and project formulation. We held at least one workshop every six months with the participation of multiple stakeholders, as well as several working sessions or smaller, focused bilateral workshops. The Conservancy selected participants for workshops based on our knowledge of the stakeholders and decision-making landscape. Depending on the goal of the workshop, different stakeholders would be invited, but several key stakeholders such as the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MADS) or the National Environmental Licensing Authority (ANLA) were always present.

Through these workshops, the conceptual foundation of SIMA – created by integrating a suite of existing software tools including Ecological Limits of Hydrologic Alteration (ELOHA) and the Water Evaluation and Planning System (WEAP) -- was designed to fit the workflow of users, such as ANLA, to ensure uptake of the technology. The Conservancy made results relevant to users by considering their most pressing needs, which, in the case of ANLA, was to comply with a regulation that included a requirement for cumulative impact reports in the evaluations of projects that require an Environmental Impact Assessment. The Conservancy understood ANLA’s need to develop an early planning exercise to avoid high-impact projects on a regional scale, and to generate a transparent system for stakeholders to understand their project decisions.

Using a basin assessment at different levels, SIMA can generate an analysis of the systems under consideration, and present results on a more refined scale to explore specific impacts. Furthermore, by allowing all users access to the same information, SIMA supports transparent decision-making and empowers users to assess the outcomes of different activities. Before the adoption of this interactive software tool, a small audience had to be physically present at a table. Now, SIMA can play the role of the table, in a virtual environment, for users to learn and contribute to from wherever they are. Now, when ANLA makes a decision about a license, the information going into that decision will be clear to all parties and the organization is better able to fulfill its public responsibility of protecting environmental resources in Colombia.

Products/Results/Outcomes

- The long-term plan for promoting HbD in Colombia includes the following components:

- Designing technical and policy strategies to help avoid, minimize, and compensate for ecological impacts of hydropower development

- Partner engagement strategy that includes meetings, workshops, training, and tool demonstrations with key decision-makers, agency leaders and technical experts to promote HbD and encourage adoption of TNC tools and data.

- A two-part implementation plan to promote HbD at the basin level and at a local level in the Antioquia region by improving institutional coordination, sharing tools and strengthening government capacity to manage basins

Building on these components and with the addition of policy and external affairs staff to the TNC-NASCA team, the Conservancy has developed a strong policy strategy to integrate HbD. Before developing this strategy, TNC worked with the technical teams of several institutions, but felt that this was not enough to ensure sustained commitment to the HbD process.4 Therefore, we organized and formalized our earlier work with technical stakeholders and defined specific outcomes for each goal to ensure that technical processes could deliver information relevant to government policy needs and promote the adoption of HbD concepts and tools.

The objective of the policy strategy is for HbD to be incorporated into government and industry practices to advance better planning and improve the siting, design and operation of dams across the entire basin. The policy strategy prioritizes incorporating conservation values into hydropower development by creating formalized agreements with government agencies and hydropower companies to design and implement pilots. The Conservancy will use the pilot program to develop a toolkit of lessons learned to inform the design of strategic basin plans for other basins in the country.

Another goal of the strategy is for government agencies to use HbD to develop scenarios for the expansion of energy projects while applying the mitigation hierarchy. Achieving this goal entails implementing pilots for the regional and basin level mitigation hierarchy and developing mandates for the energy sector as stipulated in the Strategic Plan. The adoption of SIMA as a decision support tool will be central to supporting policy components of pilot design and implementation.

The Conservancy’s understanding of the energy sector and government decision-making processes guided our identification of stakeholders that could deliver high-impact outcomes. For instance, we prioritized securing collaboration with the Mining and Energy Planning Unit (UPME) to integrate environmental and social considerations into the hydropower modeling they use to develop their Annual Energy Expansion Plan. This would be a boost to the policy strategy, because the Expansion Plan sets the trajectory for electricity generation guidelines.

To date, in support of our policy strategy, we have developed partnership agreements with MADS, ANLA, and the environmental authority for the Antioquia region (Conare). In addition, we developed and strengthened relationships with EPM, ALCOGEN, and IDEAM, as well as with non-traditional allies, such as UPME, MME, and DNP. These relationships paved the way to advance conservation objectives beyond the hydropower sector. Our consistent efforts to promote the adoption of HbD required proactively soliciting and incorporating stakeholder feedback and responding to multiple user needs. An important aspect of these efforts was to repeat the same ideas, such as ‘system scale analysis’ and ‘cumulative impact assessment’, until stakeholders began to incorporate these concepts into their own work and to influence other actors. An example of this shows in our relationship with ANLA, which has become a champion of HbD and promotes the concept with other stakeholders including the DNP.

From 2015-2016, the HbD process for the Magdalena basin has entailed more than 36 meetings with national and regional institutions to discuss and share Conservancy tools related to the development of SIMA. We also held 14 meetings with private sector companies and international consultants who made significant contributions to our modeling tools and methodology. The Bogotá based Northern Andes and South Central American (NASCA) team staff attended over nine events related to the HbD strategy, often serving as speakers, and have organized two workshops in Bogotá and Medellin for 20 representatives from both public and private institutions to learn about and test HbD tools and methodologies.

Currently, MADS, ANLA, Cornare and Corantioquia are consulting with and using Conservancy tools and adopting methodologies to identify sustainable hydropower development options. The iterative design process of SIMA, a custom-made decision support system, reflects feedback from stakeholder workshops that built on sustained engagement with government agencies, as well as private industry groups such as Acolgen, EPM, Celsia, Isagen, and consultant firms. ANLA’s adoption of tools like SIMA has introduced greater transparency into the licensing and evaluation process, a notable outcome.

Launched in March 2017, SIMA is now a publicly available tool able to engage wider audiences. Although SIMA is under development for proving, testing, and adjusting components of the system, selected scenarios and results developed with stakeholders during workshops are available on the website.

Next Steps in the Work

In the future, a key role for the Conservancy in the Magdalena will be mainstreaming stakeholder dialogue intodecision-making processes by addressing inter-sectorial planning for integrated management, made possible with SIMA.Additionally, complementary capacities and components will be added to SIMA to ensure capacity building and adoption of the tool.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Approach

Strengths: The process of implementing Hydropower by Design in the Magdalena basin demonstrates that collaboration with different partners,including governmental agencies, research institutions, basin communities, and other NGOs,strengthens the impact ofthe approach. Sustained engagement with multiple stakeholders allowed theConservancy to develop tools such as SIMA to improve the capacity of government and research institutions, and has created new opportunities for interaction between actors and institutions. Once recognized as a key advisor to decision makers, the Conservancy was able to more effectively integrate the HbD process into the hydropower development plans for the Madgalena basin. Integrating feedback from SIMA users like ANLA acknowledges their role as collaborators and as a meaningful part of the construction of the tool.

Weaknesses: While the intensive feedback process of SIMA incorporates many user demands, the tool is still missing several important capacities. For example, the hydropower sector would like SIMA to includeways tovisualize positive impacts of hydropower, such as variables for flood control and gains from added energy, rather than only highlighting negative impacts of expansion. The tool also bases its approach on the connectivity of the river network, but the presence of some natural barriers in the system are not yet included. Also, alteration from other sectors or activities (including illegal industries, such as unregulated mining) could significantly impact the health of the river andis not yet included in SIMA. Including these additional variables could paint a better picture of the full context for planning. Lastly, some policy changes require significant political buy-in and longer timelines with multiple intermediate benchmarks toprepare the political landscape. Negotiating collaborative agreements and memorandums of understanding is a lengthy and demanding process, particularly with public agencies.

Suggestions for Others Considering a Similar Approach

A primary strength ofHbDis to achieve balanced outcomes across multiple stakeholder interests and objectives, which encompass a broad range of economic, environmental and social resources. For other users considering how to best understand the interests of stakeholders and seek opportunities to collaboratethroughout the HbD process, consistent engagement can productively focus on comparatively evaluating objectives, sharing data, and building trust in the analytical tools. In the Magdalenabasin, the Conservancy did not have staff dedicated to working specifically onHbD engagement before the development of the policy strategy. Once familiar with the decision-making landscape in the basin of focus, developing a policy strategy may help guide other users in their work.

From a technical perspective, the SIMA system iseasily transferable across basins, but information input needs to be organized appropriately to take advantage of the full capacity of the software. Information used in SIMA related both to scientific data, such ashydrological modeling, and social and cultural data, is context specific.

- Restrepo,J.andKjerfve,B.(2004)The Pacific and Caribbean Rivers of Colombia: Water Discharge, Sediment Transport and Dissolved Loads. Environmental Science. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-662-07060-4_14

- International Hydropower Association (IHA). 2017. "2017 Key Trends in Hydropower." https://www.hydropower.org/2017-key-trends-in-hydropower.

- SIMA stands for Sistema de apoyo a la toma de decisiones en la Macrocuenca Magdalena Cauca

- TNC-NASCA, or Northern Andes and South Central American, isbasedin Bogotá, Colombia