Juliana Delgado, Science Coordinator, Northern Andes and Southern Central America

jdelgado@tnc.org

Background

Those tasked with managing complex systems often notethat science delivers fragmented information that is not useful at the scale of implementation (Roux et al. 2006). Developing a robust information foundation allowed The Nature Conservancyto form bridges between the domains of environmental, economic, and societal values and to investigate the complexity between these approaches to basin management. This case study highlights the process of building an information foundation to translate the interests and objectives of different stakeholders into metrics and data for the implementation of Hydropower by Design (HbD) in Colombia. Specific objectives are translated into metrics that can be measured in ways that have meaning for stakeholders. These metrics then inform data collection and selection of analytical methods.

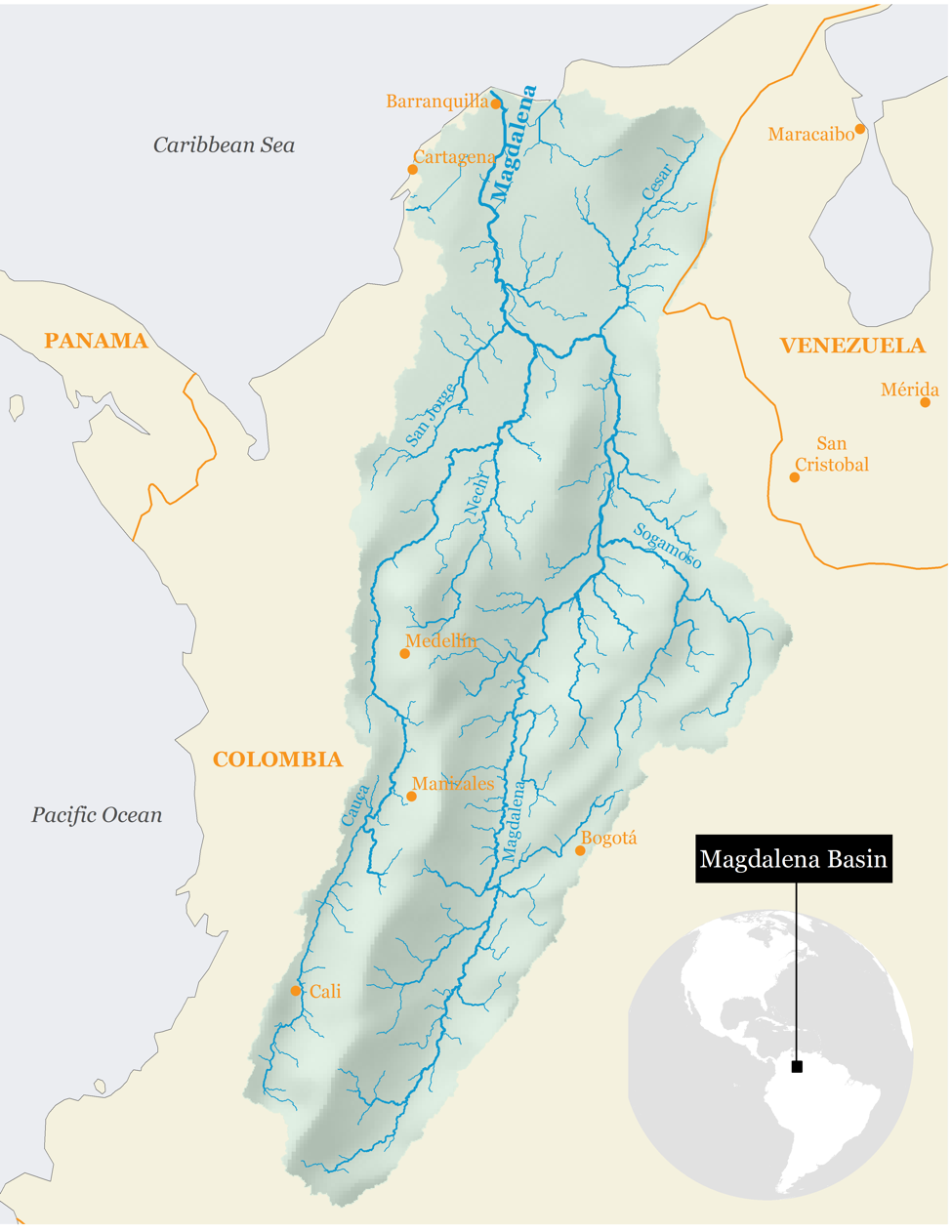

The Magdalena basin forms the economic, social, and cultural heart of Colombia; it covers 24 percent of Colombia’s national continental territory and 30 million people reside within the basin. As such, the Magdalena River basin—and its associated habitats, species, and ecosystem services—is one of the top conservation priorities for The Nature Conservancy in Colombia. Beginning in 2001, Colombia enacted a series of energy reforms and resolutions that established targets for increasing generationfrom low-carbon and renewable sources. Hydropower is by far the country’s largest source of low-carbon energy. Effectivemanagement of the basin is a national development priority, as it is closely linked to food security, energy production, and water management.

Map 1. The Magdalena-Cauca Basin and tributaries

Summary of Approach

Colombia is fortunate to have a high level of data availability in relation to other Latin American countries, with detailed information on topography, climate, and hydrology at both the basin level and for specific sub-regions. To develop metrics in response to stakeholder needs, the Conservancy collaborated with partners to transform these biophysical data into interactive models. The Conservancy expanded their information foundation by developing metrics that were useful to stakeholders, which, ultimately, contributed to the creation of a Conservation Blueprint for Colombia in collaboration with Cormagdalena, a national utility enterprise with an objective to protect the river while developing its economic potential. Conservation Blueprints are used to identify high priority conservation areas where development should be avoided, and guides action to minimize alterations and current or future impacts. Where development cannot be avoided, the Blueprint can identify possible areas to implement offsets for freshwater ecosystems.

The data informing the Blueprint came from sources including regional and Latin American datasets – such as topography and climate – as well as national land cover maps, existing infrastructure plans, and biodiversity distribution data sourced from expert knowledge. However, the Blueprint only gained minor traction because the database was not accessible for widespread consultation without detailed technical knowledge, and it provided limited ability to evaluate cumulative impacts at the detailed level required by planners.

In response to feedback on the Blueprint, the Conservancy worked to identify metrics useful to stakeholders in an effort to improve uptake. The priorities defined in the Blueprint were based on the condition of the system, expert criteria and potential sources of impacts including hydropower. These priority areas for freshwater systems were then incorporated into SIMA, a decision support tool for the Magdalena basin, and in the portfolio evaluation process as an environmental value. The feedback on the Blueprint directly contributed to the formation of SIMA, leading to a key difference: whereas the Blueprint defines results only in terms of ecology, SIMA integrates metrics for ecology, economy, and society into its multi-level framework.

Meetings and interviews with stakeholders suggested that other metrics, such as the benefits of hydropower projects or how projects could also generate positive impacts, would be useful to include in SIMA. Using feedback from these workshops and other consultations with potential users, SIMA evolved over time to present stakeholder interests in a useful format for government authorities and project developers. Decision-makers are now able to visualize risk scenarios that account for cumulative environmental, social, and cultural impacts of hydroelectric development that may not be apparent at the project or regional level. SIMA is also able to communicate livelihood impacts that may not otherwise be apparent at the highest levels of decision-making by identifying paths to achieve better system-wide results.

This comprehensive assessment approach was first tested manually to examine how components of SIMA might be applied for the design of hydropower systems in actual operation. For example, a fragmentation analysis, footprint impact and degree of regulation of the basin were done as a proof of concept application. When a user selects a possible configuration of dams in a simulation, SIMA can comparatively examine cumulative impacts on these variables that are important for ecological processes such as fish migration and sediment-nutrient flow.

The metrics we used in the information foundation to quantify the impacts of hydropower expansion with the geospatial analysis approach included: economic (related to energy generation), environmental (related to legal requirements such as protected areas and other priority conservation areas including the strategic ecosystems identified in the Blueprint), and social and cultural (related to values for communities and local people). For the social and cultural variables, in addition to common variables such as relocated habitants (population affected) or productive agricultural areas, through several stakeholder workshops we developed a classification of social and cultural values that reflects how people interact with the place they live, with an emphasis on rivers and floodplains. We also included variables to inform the national process of post-conflict reconstruction. This contributed to the creation of a dataset with more than 30 cultural and social variables.

In Colombia, in addition to its importance for economic activity and as a source of energy production, the Magdalena basin is closely tied to ethnic and cultural diversity. The use of site-specific cultural and social metrics in the information we use or our analyses is important because technical metrics often focus on impacts related to economic transformations, which was not well-connected to the cultural-environmental dimension. This approach fails to consider the impacts on the cultural rights of vulnerable populations, including indigenous communities, which may lead to the loss of cultural diversity. These metrics were developed by examining data on demographic conditions (to consider different impacts according to vulnerability and ethnicity), analyzing the productive features of the watershed directly related to agricultural and extractive production systems, conducting spatial analysis connecting the cultural identities of the watershed and the traditional economic activities associated with the basin, and assessing the relationship of the basin to the Territorial Development Plans for Peace from the Victims and Land Restitution Law (1448 of 2011).

Consequently, the sociocultural data gathered for the information foundation in the Magdalena seeks to understand the relationship of the basin and community activities such as fishing. As explained through community consultations, rural houses, chapels, and farming areas, among others, make up part of the landscape of the historic centers of the basin. This cultural heritage has been valued at the departmental and national levels. The development of demographic, cultural, economic, and environmental variables is not intended to be exhaustive, but rather oriented towards the selection of sociocultural information useful in the framework of strategic planning of the basin. These variables are a starting point to identify relationships between the basin and communities, and consequently, of cultural identities. The development of these metrics for the information foundation facilitates more detailed, holistic assessments of the impacts of hydropower development in the basin, beyond what is visible at the project impact level.

The following table has a selection from the available metrics from the information foundation that were selected by stakeholders during workshops:

Environmental |

Social |

Economic |

Demographic |

Paramos, dry forest, regional natural parks, national natural parks, wetlands, national forest reserves, regional forest reserves and second law reserves |

Indigenous communities, Afro-Americans communities and > areas |

Agricultural areas, grass areas and mining titles, energy generation (capacity) |

People affected |

This table synthetized the available metrics for social and cultural metrics:

Indicator number |

Name of indicator |

1 |

Local and regional ports |

2 |

Intangible cultural heritage |

3 |

Real estate and property |

4 |

Sacred areas |

5 |

Archaeological sites of national interest identified by the Instituto Colombiano de AntropologÃa e Historia (ICANH) |

6 |

Ground cover |

7 |

Crops |

8 |

Cattle farming |

9 |

Land tenure |

10 |

Unmet basic needs |

11 |

Education |

12 |

Relationship to the social security system |

13 |

Spatial distribution of the population |

14 |

Demographic dynamics |

15 |

Prioritized Projects of National Interest |

16 |

Mining and petroleum titles |

17 |

Potential areas for agriculture and forestry |

18 |

Sites of conflict |

19 |

Displacement |

20 |

Post-conflict zones for land restitution |

21 |

Administrative and judicial progress made towards process supporting restitution of land |

22 |

Groups seeking collective reparations |

23 |

Victims who are in the process of applying for inclusion in the Victims Register (RUV) |

24 |

Magdalena rivers initiatives where armed conflicts occurred |

25 |

Communities identified with threats to their physical and cultural survival |

26 |

Indigenous peoples identified with threats to their physical and cultural survival |

27 |

Area of existing ethnic territories |

28 |

Applications for certification of Community Councils |

29 |

Applications for legalization of indigenous territory |

30 |

Existing pre-consultation processes |

31 |

Environmental management plans with community participation |

32 |

Social organizations with initiatives to defend rivers on the Magdalena river basin |

33 |

Environmental conflicts |

Products/Results/Outcomes

Our work in the Magdalena Basin has been developed at two levels of complexity. One approach is based only on geospatial analysis, following the same approach as discussed in The Power of Rivers, considering impacts from hydropower development on three main components related to freshwater ecosystem integrity: i) loss of river network connectivity (fragmentation), ii) flow alteration (degree of regulation) and iii) reservoir footprint (direct impact of flooded area of the project). The second approach includes the use of hydrological models (such as the Water Evaluation and Planning System, or WEAP) that include scenarios of land use and climate change, and characteristics of the current and future hydropower projects, and Ecological Limits of Hydrologic Alteration (ELOHA) databases of biodiversity process such as fish reproductive migration, species distribution (including fishes and birds), and river functions (like sediment dynamics).

The process of developing tools such as SIMA required integrating many different datasets and approaches to present metrics in a format more adaptable to user needs. The process leading to SIMA began with the Blueprint, which guides conservation and restoration activities following the mitigation hierarchy. Then, beginning in 2009, the Conservancy worked with the Ministry of Environment and Development (MADS) to develop the ELOHA application. The ELOHA framework characterizes how changes in hydrological dynamics impact ecological health and defines the requirements of ecosystems so stakeholders can establish limits of alteration. This framework focused on building a hydrologic foundation of stream flow data, classifying natural river types, determining the flow-ecology relationships associated with each river type, and developing a regional approach to define environmental flow policies. 1 This two-year effort ending with a proposed classification of ecosystem types relevant to compensation policy and definition of hypotheses in support of the ELOHA framework.

The Conservancy worked with partners including the Stockholm Environmental Institute (SEI) to develop a water management tool that would be more tailored to national decision-making processes, resulting in the creation of WEAP, a hydrological modeling program for the Magdalena basin.2 To develop this application, SEI and the Conservancy developed software to model basin dynamics, and simulate how dams influence basin hydrology and river-floodplains-wetlands dynamics. This resulted in generating software changes to incorporate other tools from the Conservancy, such as the Indicators of Hydrologic Alteration (IHA) and other new modules including one that represents the transfer of water between the river to the floodplains and wetlands. WEAP is able integrate river basin and water management, developing from a “project by project†to a whole system approach in response to evolving user demands.

From these models, partners could use the software to envision many possible futures of the basin and compare impacts on biodiversity and river flows. For instance, using IPCC climate data, users can model the interaction of local hydropower infrastructure and hydrology of the basin under different climate scenarios. However, while WEAP was developed as a decision support system (DSS) focused on water management, it did not incorporate all of the desired components from users, so the Conservancy sought to build another DSS that could integrate physical, environmental, ecological, socio-cultural and economic variables, and emphasize freshwater ecosystems. As we continued work on improving these models, we also developed the second iteration of ELOHA as well as the variables used in The Power of Rivers, including connectivity and network fragmentation. This process contributed to the creation of SIMA, which was designed over the course of 2015 and developed for the web from 2016-17. The Conservancy and the Centro de Recuperación de Ecosistemas Acuáticos (CREACUA) incorporated the WEAP applications, along with ELOHA databases, the Blueprint, Barrier Assessment Tool (BAT) analysis, other databases (including social-culture, environmental, and climate) and HbD tools into forming the foundation for SIMA.

A key outcome of this process is that MADS incorporated Conservancy guidance to incorporate the ideas and concepts of HbD into its Strategic Plan, of the Magdalena basin a key policy instrument that guides other basin management plans and territorial planning at a municipal scale. The Plan includes two guidelines that use Conservancy tools to support planning decisions to avoid impacts on natural ecosystems and resources, and identify stretches of river to protect as “no-go zones†for new hydropower infrastructure in sub-basins. This Plan will serve to improve policy for freshwater systems to reduce impacts. In the future, SIMA will address some of the limitations of the Blueprint by not only defining the selection of priority systems, but also allowing stakeholders to help identify important systems.

Next Steps in the Work

A key next step for strengthening the information foundation is to work with the Colombian government to establish a pilot exercise as part of guidelines included both in the Strategic Plan of the Basin and the inter-ministerial agreement between MADS and with the Ministry of Mining and Energy. This will include updating data, meeting with key stakeholders needed for developing an early planning pilot, and incorporating new metrics such as a project’s distance to roads or interconnected grid, and including natural barriers and small hydropower dams. This pilot may guide a hydropower expansion plan that incorporates HbD concepts to reduce environmental and social risks.

In parallel to the pilot, the Conservancy will also continue our work in collecting relevant data, some identified through feedback from basin stakeholders. To further improve upon the information foundation, the Collaborative Partnership, a collective action strategy, was formed by the Conservancy, MADS, the National Environmental Licensing Authority (ANLA), the regional environmental authority Conare, Acolgen, and the Colombian Institute for Hydrology and Meteorology. In December 2016, the Partnership began to strengthen tools for early planning, address barriers to the national offset scheme, and manage data in the basin. By working with the Partnership, the Conservancy will continue to improve scientific understanding of basin processes, translate interests into effective metrics, and systematically deliver information to users. For instance, working with ACOLGEN (the association of hydropower generators) and EPM to become champions of HbD and SIMA may contribute to broad acceptance and mainstreaming of HbD principles in the sector.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Approach

Strengths: Regular meetings with stakeholders to incorporate ideas for new metrics facilitated an iterative process whereby each group felt valued. Working with stakeholders to collaboratively define metrics also entailed continuing to build the information foundation for environmental and social values.

Weaknesses: This approach underlines the importance of translating complicated scientific information into understandable formats for decision-making and practical implementation. However, this process of simplification is slow, and requires coordinating among many organizations. This means that information is often incomplete.

Suggestions for Others Considering a Similar Approach

For others seeking to translate stakeholder interests and objectives to metrics and collect useful data, it is important to work with official institutions and use their standards and protocols to develop or manage information. Trying to complement or align the efforts of generating new data with other initiatives already in place is also key to presenting data and tools in a useful format. The lack of coordination of institutions working in the sector and difficulties in inter-agency communication may present challenges to building an information foundation. Therefore, partnerships, not only with direct stakeholders, but also academic and research institutions, may help to further iteratively develop and validate data and tools.

Furthermore, developing specific environmental, sociocultural, and economic metrics can help to build an information foundation that contributes to a holistic assessment of the basin beyond individual project impacts. Triangulating data sources – including technical biophysical data (climate, topography, sediment flow, etc), social vulnerability indicators such as poverty levels, spaces of cultural and ethic history such as archaeological sites and indigenous territories, and identifying biodiversity priority areas – may help to develop more nuanced information relevant to the interests and objectives of different stakeholders. Selection of variables – demographic, cultural, economic, and environmental – should be done in collaboration with key stakeholders.